August 7-9, 2018

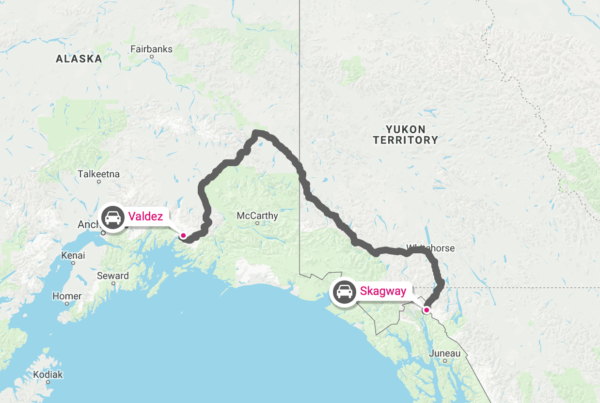

Skagway is in southeastern Alaska, 396 air miles or 753 road miles from Valdez, our previous destination. The highway took us through Yukon Territory and British Columbia.

As we neared the border with the U.S., we saw some of the 600 fires that plagued British Columbia over the summer.

Fires along the Tutshi River

Skagway is from a Tlingit expression meaning roughed-up water. Billy Moore was an early settler of European descent in the area. He had been a member of an 1887 boundary survey expedition and recognized that the Alaskan mountains were similar to mountain ranges in South America, Mexico, California and British Columbia where gold had been found. He homesteaded 160 acres at the mouth of the Skagway River because he thought it would be the beginning of the most direct route to potential gold fields. He built a log cabin, a wharf, and a sawmill and pioneered a path over the mountains.

Gold was discovered in 1896 in the Yukon, 600 miles away, and Skagway became one of the most popular staging locations. By the spring of 1898, Skagway had around 8,000 residents, was Alaska’s largest city, and had about a thousand prospectors passing through the area each week. Skagway’s population today is about 1,000 people. They host about a million visitors each summer.

Skagway hosts multiple cruise ships every day through the summer and during daylight hours was crowded with passengers and tour buses.

Four transportation modes: pedestrian, auto, train, and ship.

We stayed in a small campground right on the harbor.

One of the more interesting buildings in town was home to the Fraternal Order of the Arctic Brotherhood, formed in February 1899 during the Klondike gold rush. Its facade of more than 8,000 pieces of driftwood dates to 1901. The building now houses the Skagway Visitors Center.

White Pass and Yukon Railway

Our first excursion was a train ride on the White Pass and Yukon Railroad (WP&YT) to the summit of White Pass. When gold was discovered in the Yukon, the White Pass was one of two routes stampeders took to the goldfields. Skagway founder Billy Moore and Skookum Jim Mason, one of the discoverers of the first gold found in the Yukon, first identified the route over the pass. The White Pass route was shorter than the competing route over the Chilkoot Pass, and pack animals were used on the White Pass Route. Jack London wrote about the trail:

The horses died like mosquitoes in the first frost, and they lay rotting in heaps. Men shot them, worked them to death, and when they were gone, went back to the beach and bought more. Their hearts turned to stone, those that did not break, and they became beasts, the men on the Dead Horse Trail.

One entrepreneur built a toll road twelve miles up White Pass Canyon, but no one paid the toll. In May 1898, construction began on a railroad over the pass using the toll road. 35,000 workers, paid 30¢ an hour, worked for 26 months to construct the railroad. They used 450 tons of explosives clearing the bed for tracks that would raise 3,000 feet in elevation in 20 miles.

Skagway from the train

Conductor

We crossed this trestle.

This bridge into the mist has been replaced.

There’s not much space between the train and the rock face.

One of the waterfalls on the route

Out of the tunnel

Flags (U.S., Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon Territory, Canada) at the summit

Fireweed in the mist at the summit

Souvenir sales

The railroad was one of the main supply lines for construction of the Alaska Highway. Trains carried freight until 1982 when demand for rail transportation declined. The railroad was reopened in 1988 as an excursion.

Gold Rush Cemetery and Lower Reid Falls

Our train trip passed Gold Rush Cemetery. We went back with the Jeep for a closer look.

Here’s Dave (in one of our few souvenirs–a White Pass and Yukon Railroad hat) beside what is probably the world’s largest gold nugget.

Soapy Smith led a gang of conmen, taking advantage wherever he could. He operated a telegraph office, charging prospectors $5 to send a wire back home–even though there were no telegraph lines in Skagway. He was killed in a shootout with Frank Reid, the town surveyor who had laid out the townsite and named Skagway’s streets. Reid’s grave marker proclaims “He gave his life for the honor of Skagway”. Smith’s grave has his name, age, and date of death.

Reid’s grave

“Soapy” Smith’s grave

Many of the railroad workers were Chinese.

View of the cemetery

A brief walk took us to Lower Reid Falls.

Dyea Townsite

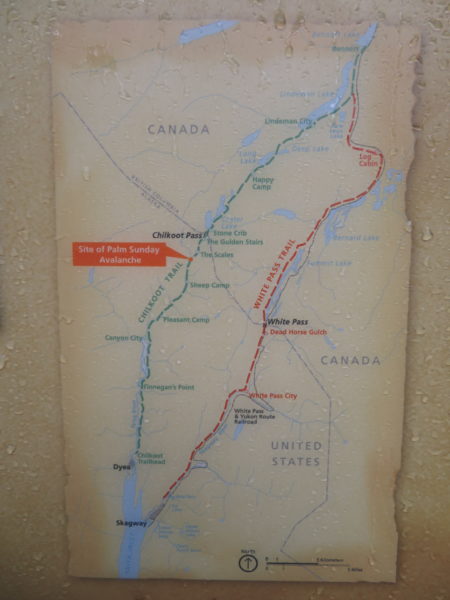

Dyea (pronounced Dye-ee) is one of five locations that make up the Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park. It’s about 10 miles from Skagway. Historically, it was a summer camp for the Tlingit First Nation. They built the Chilkoot Trail to allow trade. [Dyea means to pack, and Chilkoot was a Tlingit tribe.]

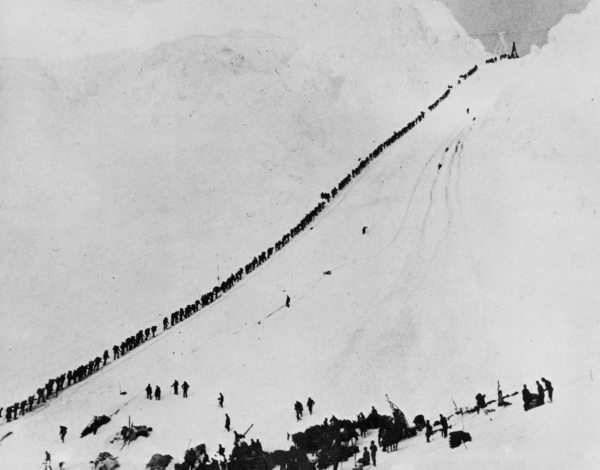

Many prospectors headed to the Klondike goldfields chose the Chilkoot Pass. Before traffic on the pass overwhelmed them, Tlingit men would help pack and carry supplies up the 1500 steps cut into snow and ice. Each person was required to bring a year’s supplies so many trips were required.

Wikipedia image of the Golden Staircase up the Chilkoot Pass

By 1897, Dyea was a city of 10,000 with 150 businesses including 19 freighting companies, 48 hotels, 47 restaurants, and two newspapers. Taverns outnumbered churches 39/1.

Two factors led to the decline of Dyea and the Chilkoot Pass. First, an avalanche on the pass in April of 1898 killed 60 people. And, second, the completion of the White Pass and Yukon Railway provided an easier and safer route to the goldfields. By 1900 Dyea’s population was 250, and by 1903 only six people lived there.

Few traces of Dyea are visible today. We followed a self-guided brochure until we caught up with a ranger conducting a tour.

The A. M. Gregg Real Estate office was one of seven in Dyea. The building collapsed in the 1970’s, but local residents propped up its front.

The Taiya River washed away many town artifacts but the river has stayed on the other side of the valley for about 50 years, allowing vegetation to grow in the meadow. This was the site of the 115-room Olympic Hotel.

We saw evidence that bears are current inhabitants of the area.

The site of the Vining and Wilkes Warehouse is now high and dry but it was on a tidal flat in 1898, partially as a result of [today’s vocabulary word] glacial or isostatic rebounding. During the last ice age, this area was covered with a glacier 4,000 feet thick. The weight of the glacier has been removed and the land has risen in response–about 3/4 of an inch per year, or eight feet over the last hundred years.

Foundation timbers from the Vining and Wilkes Warehouse

In May 1898, owner A. B. Wilkes described what it was like in his warehouse.

You can imagine what it was like to have a whole boatload of gold-crazy men crowded into it . . . all demanding their freight at once. It was frequently necessary to have six-guns in evidence to prevent mob action.

When we found them, the ranger and his group of walkers were watching a tree on the riverbank which they thought was about to fall into the water. On our drive back to Skagway, we saw what may have been that tree in the river.

Skagway Museum

We’ll share two pictures from this museum.

A mammoth tusk

A table from the Arctic Brotherhood, decorated with driftwood

Our last adventure from Skagway was a trip to Juneau which we’ll include in a separate post.

1 Comment

Jay Waters · November 5, 2018 at 8:19 am

Sitting on a riverbank waiting for a tree to fall in. Beats watching the news! Saw your post on Facebook, glad you’re having a safe trip. Happy Thanksgiving!