June 29-July 1, 2018

Klondike Highway, 323 Miles

To get to Dawson City, 330 miles north of Whitehorse, we left the Alaska Highway temporarily and began the Klondike Loop. We soon came to an overlook for the Five Finger Rapids where four islands divide the river into five channels. Before a one-to-two foot drop in the rapids was corrected, sternwheelers had to winch themselves through the area.

We enjoyed blooming wildflowers at the side of the highway.

Dawson City is definitely one of the most colorful and eclectic cities that we have visited. Located on the banks of the Yukon River near its confluence with the Klondike River, it is a mixture of First Nation heritage, Gold Rush history, active mining and tourism industries, and a thriving art scene. Dawson’s past was created by the Beringian Ice Age period that formed the unique landscape and placer gold deposits, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in indigenous people who lived in this area for centuries and the Klondike Gold Rush that put this town and the Klondike River on the tongue of stampeders worldwide.

The road to Dawson City was a bit dusty.

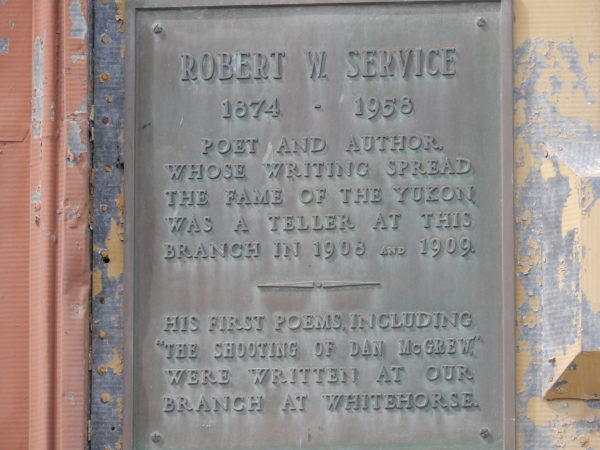

Dave’s fascination with the area and its history came from reading Jack London’s Call of the Wild when he was a young boy. London and the poet Robert Service both came to Dawson during the Gold Rush, and the cabins they stayed in are still in town.

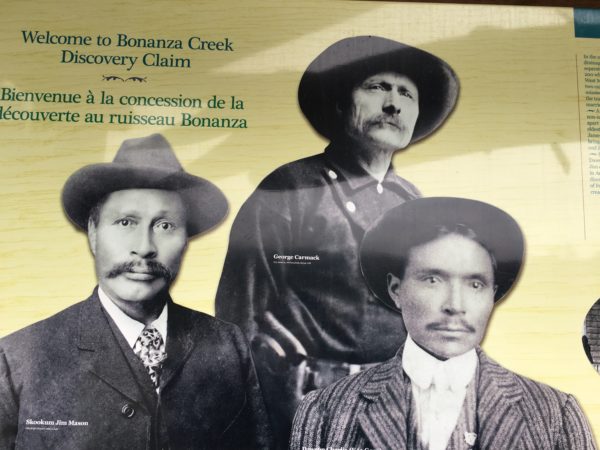

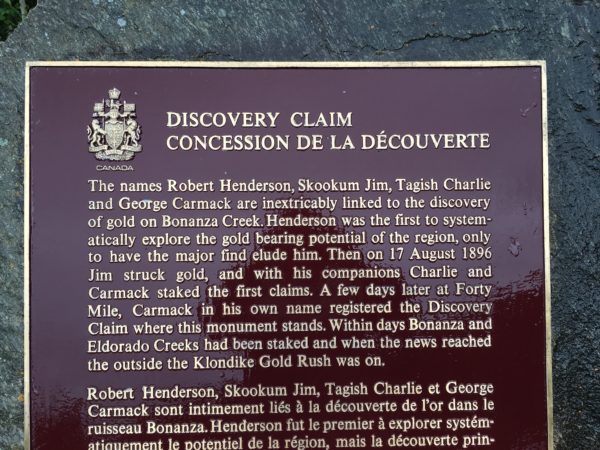

On August 17, 1896, three Yukon “sourdoughs” (a sourdough is someone who has spent a winter in the frigid North) named George Carmack, Dawson Charlie and Skookum Jim, found gold on Rabbit Creek (now Bonanza Creek), a tributary of the Klondike River.

Word quickly spread to about 1,000 prospectors, miners, Northwest Mounted Police, missionaries and others who called the Yukon home, who rushed to stake claims to the best ground. Two of these residents, Joe Ladue and Arthur Harper, who had been trading in the Yukon for years, purchased, staked and established the townsite of Dawson which was named for Canadian geologist George Mercer Dawson.

The church has supports under it to keep it from collapsing.

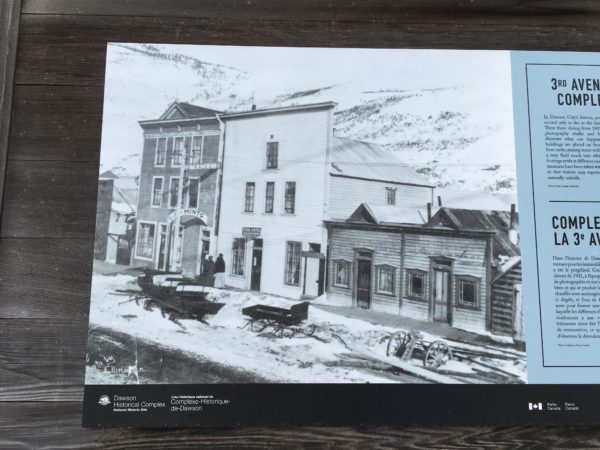

News of the gold reached the outside world in July 1897 when the steamships Excelsior and Portland reached San Francisco and Seattle with the successful miners carrying the infamous “ton of gold”. News spread that gold nuggets could be picked up off the creek floor and an unprecedented stampede of an estimated 100,000 people set out for the Klondike. The expenses and hardships of the treacherous journey quickly caused many to give up and return penniless to their homes. In 1898 Dawson grew to thirty thousand prospectors, miners, shopkeepers, saloon owners, bankers, gamblers, and prostitutes, most living in tents or primitive cabins. Most arrived to find the good claims had all been staked in the previous two years and turned to other endeavors or returned home. Money was not an issue in Dawson as gold was in abundance and new businesses, hotels, banks, saloons, churches, and a theater quickly sprang up. Overnight millionaires could purchase the best foods, drink, and clothing all at very high prices, from stores that made fortunes “mining the miners”.

The Commissioner’s Residence was built in 1901 and was home to the vice-regal head of the Yukon Administration.

In 1899 gold was found on the beaches in Nome, Alaska and many of the people who came to the Klondike seeking fortune left Dawson in a new rush.

Dawson’s population of 30,000 in 1898 declined to 9,000 in 1900 and 900 by 1920. The original claims were soon bought out and consolidated by companies that brought huge gold dredges to the area that mined the Klondike River valley and its tributaries for decades. The Klondike area which is still producing gold has yielded an estimated 14,000,000 ounces of gold worth more than two trillion dollars.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in (meaning people of the river) is the First Nation group based in Dawson City. Their citizenship of roughly 1,100 descendants of the Hän-speaking people have lived along the Yukon River for millennia include a diverse mix of families descended from Gwich’in, Northern Tutchone, and other indigenous tribes. The Hän word Tr’ondëk was heard by the prospecting newcomers as Klondike and is now used for the River and area.

One of the principal salmon fishing camps used by the Hän people of the nineteenth century was located at the mouth of the Klondike River. Early traders reported about 200 people living at Chief Isaac’s fish camp at Tr’o-ju-wech’in in the years just prior to the Gold Rush. The arriving gold rushers quickly overran the area and pushed the indigenous people off their land. When the Tr’ondëk Hwech’in left Tr’ochëk in the fall of 1896, they moved across the river to the new town of Dawson. Over the winter, Chief Issac, church and government officials determined that they should move downriver to the village of Moosehide. By spring they were building cabins and a new community. An impressive orator, Chief Issac spoke frequently in Dawson, and while he welcomed the newcomers, he never failed to remind them that they prospected at the expense of the original inhabitants and that they had driven away the game they lived on and had taken over their land. In 1902, he traveled to San Francisco and Seattle to share his plight and story. Chief Isaac foresaw that his people would lose much of their culture under the growing influence of the missionaries and non-native society. To preserve their culture, Isaac entrusted many Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in songs and dances to the Alaskan Hän people for safekeeping, along with the gändäk or ceremonial dancing stick because the governing bodies in Canada, in an attempt to enculturate the indigenous people, forbade the use of their language and ceremonies. Today, as an important part of cultural renewal, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in are relearning these songs and dances from their Alaskan neighbors.

In Canada, the First Nations did not obtain the right to vote until the 1960’s. The Yukon First Nations presented a document called “Today for Our Children Tomorrow” to the Canadian government in 1973 as a basis for negotiations. Finally, in 1997 they regained ownership of their traditional homeland. In Dawson, the Dänoja’ Zho Cultural Center presents the heritage of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in in displays, interpretive programs, and events.

Our guide was Tr’ondek Hwech’in and shared her culture and traditions.

Dawson grew up in the shadow of a scar-faced mountain called Midnight Dome. There are trails and a road to the top which provides a good view of the town and the surrounding rivers and mining areas.

Dawson City on the banks of the Yukon River from atop Midnight Dome.

A view up Bonanza Creek from Midnight Dome.

White Pass and Yukon steamers were often berthed at the town’s docks. These boats were part of a fleet of 250 paddle-wheelers which plied the river between Whitehorse and Dawson. The SS Keno was the last sternwheeler on the Yukon River. It made its final journey to Dawson City on August 20, 1960. It can still be toured at the city’s docks.

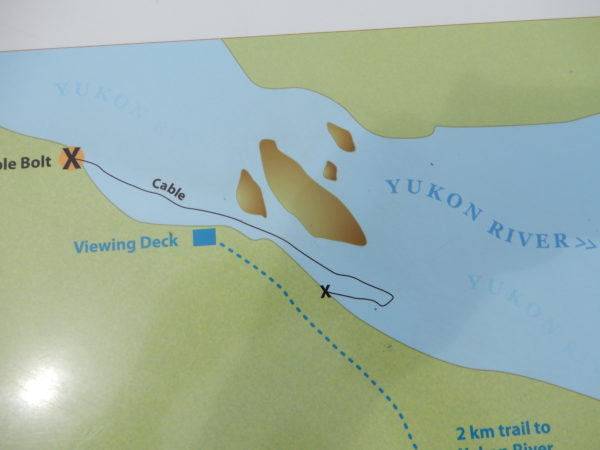

Dawson also had a number of sternwheelers that were drydocked on the opposite side of the Yukon about two miles downstream. The area is now a paddlewheel graveyard with seven ships in various stages of decay rotting away in the woods by the river. To get to the graveyard, we had to take the George Black Ferry across the river and then walk down the riverbank until we spotted the wrecks in the woods. [We had learned about the site from Geocache. We found the cache!]

The Dawson City Museum is housed in the former Legislative Assembly building that was used until the capital of the Yukon Territory was moved from Dawson City to Whitehorse in 1953. The Museum has exhibits that guide the visitor through the Klondike years, the Gold Rush, and the boom and bust of Dawson City. The museum has tours, movies, a real courtroom and a gift and coffee shop. It also has a small train and transportation museum in a separate building.

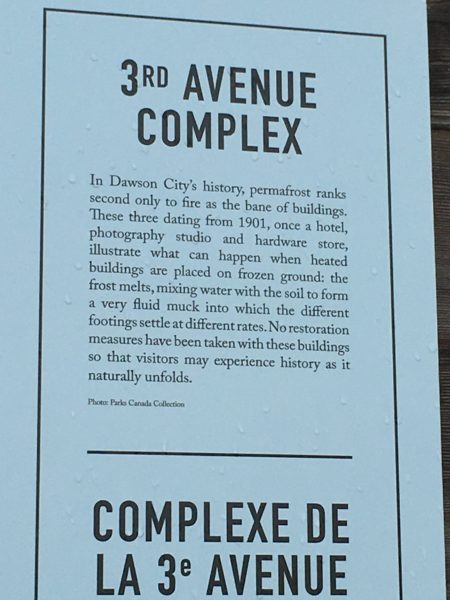

Parks Canada has assumed ownership of many of the historic buildings in Dawson City and has restored some and maintained others.

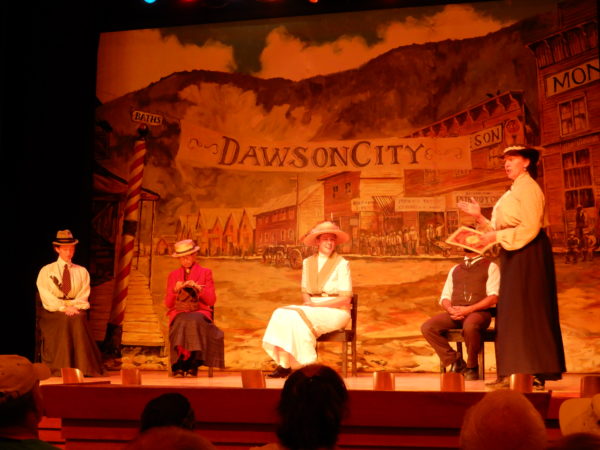

The Parks Service has 12 different tours available, many of which are conducted by rangers in period costumes. We managed to take six of them while in Dawson and we were pleased with the experience. The “Then and Now” walking tour took us inside some of the historic buildings where we were visited by a costumed ranger who related what it was like in Dawson in 1898.

The “Behind the Scenes” tour allowed us to get up close and personal with pieces of Klondike history, handling artifacts that are usually off-limits to the public.

The “Hike through History” began at the Robert Service cabin and hiked up the hill through spruce trees to a viewing point above the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers while uncovering Dawson City’s past. We were the only participants on this tour so we were able to ask as many questions as we liked and stop whenever we saw something interesting.

“The Greatest Klondiker” was a show in the Palace Grand Theater, Dawson’s original playhouse. Four Klondikers appeared on stage, introduced themselves, told how they made their name in the town, and tried to convince the audience that they were the Greatest Klondiker. The competitors were a journalist, a store owner, the wife of the territorial governor who went on to become a member of Parliament, and a businessman.

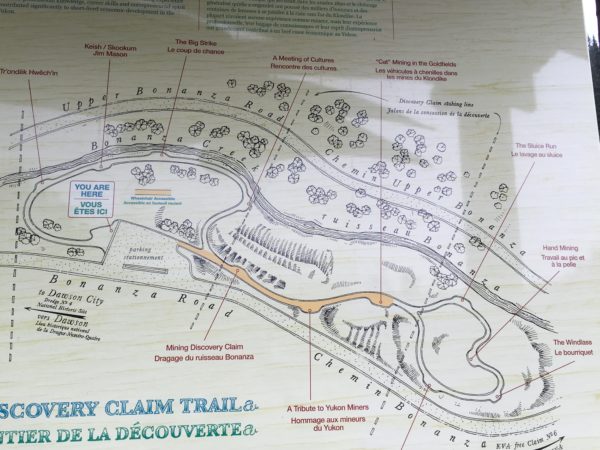

Near our campground outside of town was the road up to the Bonanza Creek mining area. Parks Canada has a Discovery Claim interpretive trail that shows where the Gold Rush began. At Claim Number 6 on Bonanza Creek, you are stilled allowed to pan for gold [we lacked the equipment for this].

The most interesting relic on Bonanza Creek is the Dredge No. 4 Historic Site. Not long after gold was discovered, dredges were brought in to the Yukon, the first being built in the fall of 1899. One of two dozen dredges that worked the area, Dredge No. 4 rests on Claim No. 17 Below Discovery on Bonanza. [The first claim is “Discover” and subsequent claims are “Below” (downstream) or “Above” (upstream)]. Dredge No. 4 is the largest wooden-hulled, bucket-line dredge in North America. It was built on Bonanza Creek and operated until 1959.

Dredge No. 4 is 2/3 the size of a football field and eight stories high. It displaced over 3000 tons and each bucket had a 16 cubic foot capacity. It could dig 48 feet below and 17 feet above water level. It was electrically powered from the company’s hydro plant on the Klondike 30 miles away. The dredge moved along on a pond of its own making, digging gold-bearing gravel in front, recovering the gold through a revolving screen-washing plant, and then depositing the gravel out the stacker at the rear.

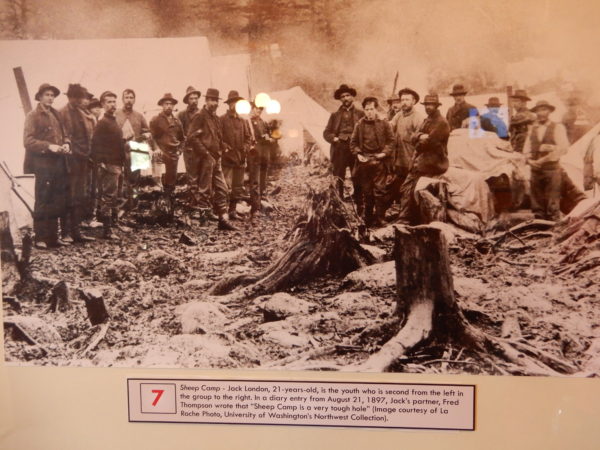

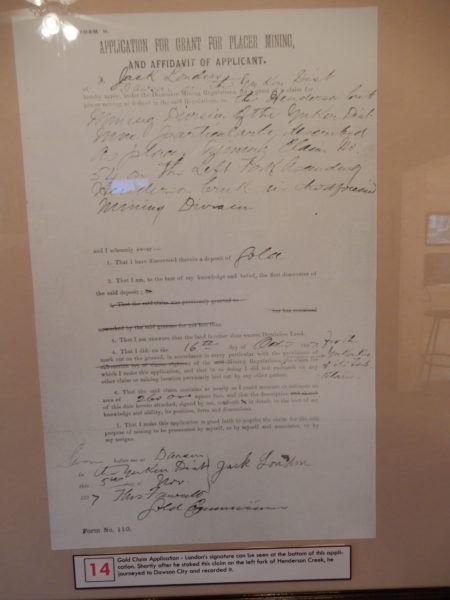

On July First, we visited the Jack London cabin and museum. Jack London came to the Klondike in 1897 to search for gold. The cabin he stayed in was discovered by trappers on Henderson Creek. It was rediscovered by historian Dick North who had it dismantled and moved to Stewart Island. In 1969, two replicas were build using logs from the original cabin, with either the top or bottom of each cabin being original. One cabin is located at the Jack London Interpretive Center in Dawson City and the other is in Jack London Square in Oakland, California. The museum has interpretive presentations about London’s adventures in the Klondike, and a collection of photos tracing his journey to the Klondike and links his literature to the people and events that occurred during the Gold Rush.

Oh, Canada! in Dawson City. We were in Dawson City for Canada Day and the city was celebrating with special events. The 20th annual Yukon River Quest is an endurance paddling race that started in Whitehorse on the 28th and finished in Dawson on the 30th.

They also had a golf tournament, artist and farmer markets, and a Frontier Ball.

On Canada Day, July 1, they started the day with a parade, bike rodeo and floats, followed by a flag ceremony and the singing of O’ Canada! Parks Canada handed out small Canadian flags for everyone to wave.

A community barbecue was free for all in the park, with live music, cake and watermelon, and fun and games for the kids. Following the picnic, you could try your hand at a cricket, a game that’s been played in the Klondike since 1901, have a swim at the community pool, and take in the Greatest Klondike Canadian competition at the Theatre. Canada’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau, flew into Dawson that evening.

In between all of these events and activities, Dave searched for a series of geocaches hidden by Parks Canada in the Gold Fields and around the historic sites in Dawson. He collected a prize for the caches he found.

Finding a geocache under an historic warehouse.

Dawson’s old cemetery, nestled between the town and the base of Midnight Dome mountain is dedicated to the early settlers. Y.O.O.P. stands for Yukon Order of Pioneers.

Leaving Dawson City for Alaska via the Top of the World Highway one must use the George Black ferry as there are no bridges that cross the Yukon River. The ferry is free and runs from May-September. We took the ferry twice, once in the Jeep to see the paddlewheel graveyard and again in the RV to continue our journey to Alaska. The ferry grounds itself on the river bank which is constantly being eroded by the river and replenished by bulldozers pushing new gravel into the river. The wait to board the ferry, especially in the morning can be several hours long.

2 Comments

jay Waters · August 12, 2018 at 12:18 pm

I believe this is one of your longest entries; you must have had a really good time! I love Robert Service poetry.

Susan · August 13, 2018 at 1:45 pm

I am enjoying your adventure very much!